24.39 Classic Photography Fair Attracts Vintage Photography Buyers

Lisa Holden: A More Complex Feminist Path, Exploring Emotion, Identity and Vulnerability

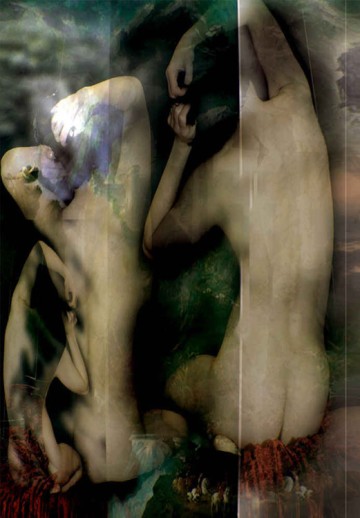

Reclining II, Chromogenic print with acrylic paint and varnish on Dibond mount with UV laminate.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, I made several visits to the Netherlands. I had good reason to. In addition to new museums opening up--Huis Marseilles and Foam in Amsterdam, the country was at the forefront of digitally manipulated photography and staged photography, after which both approaches spread internationally.

Both terms could be used to describe the work of Lisa Holden. Originally from the UK, she moved to Amsterdam to study at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy. Her work, however, was diametrically opposed to the work of her Dutch peers. The latter would go over every pixel in their images, whereas Holden would use pixelated images taken with a cheap camera, use photocopiers, splash varnish and paint, rephotograph and scan, manipulate in her computer. Unlike the others, she didn't use models for her staged images, but herself instead. Putting herself on the line.

But there was another difference. What brings an image into being? An awful lot of the Photoshopped and staged imagery that was made at the time struck me as eye candy, specious, vacuous, immediately grabbing your attention but actually pretty empty. In the case of Holden, it has always been the case that it's the emotions that have driven her images into being. And ultimately, why they stay with me.

When we first spoke some 20 years ago, you told me that identity and your search for it were central to your work, and that it had a lot to do with being adopted at an early age.

"I was born in a children's home and was adopted at six weeks. My birth mother left me when I was four weeks old. Adoption can leave behind an enormous sense of disconnection. Society is very unforgiving if you are someone who feels on the outside. One of the reasons my work connects with others is that there are so many people who feel disconnected or alienated, regardless of family circumstances. And it seems as though the more connected we become, the more isolated we feel."

Garden (Tree): I found myself drawn to the Pre-Raphaelite painters. I didn't like the work but was fascinated by their portrayals of women.

As a child, and going into your teens, what drew you to art?

"I wanted an escape, and I read and wrote stories, and I drew. Back then, I had very eclectic tastes. I liked Hieronymus Bosch and a lot of the Surrealists. I was brought up near Liverpool, and I used to go into the city a lot by myself, to the Walker Art Gallery. They have a big collection of Victorian art, and I found myself drawn to the Pre-Raphaelite painters. I didn't like the work but was fascinated by their portrayals of women. They had flowing hair and huge lips, and they were dressed in medieval robes and were often posed with flowers. It was all a bit ridiculous. When I looked into Dante Gabriel Rosetti, I found that he actually looked a lot like the women he painted, and I think he was portraying himself in a way, which I found very interesting. It was a sort of slippage of identity. His women were strong-jawed; they had a certain power and an almost archetypal presence, and that appealed to me."

It's interesting that you were drawn more to historical work rather than contemporary work.

"I think I was looking into the past and to art history to find a sense of genealogy. I found my lineage by looking at people from the past who were artists or photographers. I drew a lot of portraits. I started taking life drawing classes and did a lot of work in charcoal, pen and ink. I also had a camera when I was quite young. I was about seven when I took my first picture. It was of my adoptive mother just as she was waking up, because I was afraid of her, and I think I wanted to 'freeze' her."

What was the atmosphere in your adoptive home?

"Dysfunctional. I would describe my mother as having a narcissistic personality. My father once hit my sister with a riding crop. I was the eldest of two adopted daughters. We weren't related, and I was the one who had the capacity to go to university. Our parents thought that was great, but at the same time when you're the 'golden child', you're almost the source of food for your parents. In my teens, my mother didn't speak to me for three years. She gave me the silent treatment because I did things differently to her. I never even had a key to our house. I had to ring the doorbell to get in, and once in, I had to account for where I had been. My mother was a probation officer. She often threatened to make me a ward of the court because I was disobedient. I mean, I never did anything, but she said I would turn out just like my birth mother, end up getting pregnant at 14 – my mother was actually 21 when I was born – and, well, be a whore."

How did you cope?

"I escaped as soon as I could. At 17, I left and went to live with a friend in Crosby whose family had a fairly big house and kindly let me stay in a room in the attic. I then left to study at university, not art but English literature. Following that, I went to London, worked as a secretary, and ended up in publishing, working for small firms, including Jonathan Calder, who published authors like Samuel Beckett and William Burroughs. I decided to study art, but having used up my grant in the UK, I moved to Amsterdam to study at the Gerrit Rietveld Academy."

Siren: "It wasn't really about gender fluidity, as the term is used now, more about how identity is a construct and how the face and body are a facade."

What kind of work were you doing at the Academy?

"At the time, abstraction and conceptual art were the big thing. I'd been thinking about studying printmaking, but ended up taking a course focused on performance and conceptual art. I started making videos, voice recordings, and then sound installations. I would have about four voice recordings, of me telling a story with a lot of pauses in between. And then I would have speakers positioned throughout space, so that when you were standing in the space it was almost as though you were kind of moving through it. After that, I started doing performances, transforming myself into a man, into different women. It wasn't really about gender fluidity, as the term is used now, more about how identity is a construct and how the face and body are a facade. It was when I was at art college that I met my birth parents for the first time, and part of my performances was about me working through that, putting fragments back together."

What was meeting your birth parents like?

"Heart-breaking. They had split up before I was born. It turned out that my mother was from South Africa, my father from Austria. They were really just interested in themselves. When I met my father, he and his wife were going through a difficult patch. He went next door and came back with some photographs of my mother from years earlier. His wife had never seen them. He threw them on the table, like a hand of cards, to show his wife. He used my presence as an excuse, basically, to finish with his wife, I think. I was just standing there as a witness to this ridiculous scene. There was this sense of enactment and the performative nature of these situations and emotions. His wife said, "She can't be your daughter. You're blonde and she's dark." It was a farce, but I'd been brought up in a home that was like a farce, so it just went on in the same weird way. Then I went to see my mother in South Africa, and her main interest in me was, as a go-between, to reconnect with him. She even gave me a letter to give to him. I was devastated. I'd always thought, 'Oh, I'll find my birth parents; it'll be amazing. I'll finally belong. Home at last.' I was so naïve. In many ways, meeting them was one of the worst experiences of my life. I couldn't help thinking life was telling me that I've always been meant to be without parents, that I was fated to bring myself up. And that's basically what I did. And my work has been a way to do that, giving me the tools to make my own place in the world."

Photography and, later, video played an important part in performance art, for the Vienna Actionists for example. It went beyond documentation. When did photography and video enter your own performances? And how did it then transform into art works?

"It was quite soon after I started doing performances. It was very easy to make videos thanks to the small, digital cameras. Initially, I started making videos of myself performing just to see how I came across. But then I began extracting stills from the videos. I was interested in the texture of the image because the stills were grainy, and it was almost like a Polaroid-type effect. And I've always really loved Polaroid. The images seemed to capture life in a different way; the images had a different kind of energy. After that, I started working with a very cheap digital camera, but the images were heavily pixelated. In the beginning, I saw the pixels as flaws and thought, 'Oh, I've got to get rid of these and smooth them away.' But then I decided to leave them in. I realized the pixelated surface, with all its fractures and disruptions, echoed the spirit of the work."

Pink Poppies: "Putting something different in is also part of the thread that runs through the work; it cannot be tidied up, because it's unfinished. It's raw. The threads are fraying at the edges. It's about the emotions that come through."

Looking at those early works. They're confrontational and actually very complex, involving video stills, photocopying, paint even. What techniques were you using at that time?

"I would start with a digital image and print it out on my small A-4 printer. I would then splatter varnishes or acrylics on it or simply draw with pencil. Next, I would rephotograph that print, or I would scan it in, and then I worked on it again in the computer, create layers and continue to go from there. That way, marks and certain bits of information would be altered, be a bit deformed, fade a little bit, make interesting textures and I liked that it was all a bit accidental, that I wasn't always in control. I enjoy polished work by other artists, like Cindy Sherman or Zanele Muholi, but I can't work like that myself. I like to get my hands dirty with paint and flick stuff and tear things apart. Putting something different in is also part of the thread that runs through the work; it cannot be tidied up, because it's unfinished. It's raw. The threads are fraying at the edges. It's about the emotions that come through."

You were also using yourself as a model at the time, laying yourself on the line. Did you even consider using another model?

"Not really. I had used my own voice for the voice recordings, and I simply continued. I used wigs, most of them really cheap and tacky, to transform myself, and would put on thick, really thick layers of stage make-up, almost like paint. I wasn't scarring myself, but that's what it looked like. Another reason was that when I had taken photographs of my dysfunctional family, it began to feel dishonest. That I was using them, that I had, in a way, spied on them. I also felt that the camera was between me and the world, a kind of shield, something I hid behind. Instead, I decided to capture something of the absurdity and the clownishness in my family by enacting it myself. In some images I have huge red blobs on my face, makeup gone mad."

At the time, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Netherlands was at the forefront of manipulated photography, every pixel polished to perfection, as in the work of Inez van Lamsweerde for example. Your work went in the opposite direction. How was it perceived in the Netherlands?

"I had a difficult time with it, very difficult. Then I started doing things that involved collaging elements from painting and that type of thing, and that really wasn't accepted either because it was super figurative. It was different for Inez because she was an actual photographer. She worked in fashion, so she had that crossover. My work just didn't fit into what the others were doing. I also think my aesthetic was too personal. It was not exactly surreal, but it played with other elements of art history and mythology. Not what the others were doing, so it was hard to get a foothold."

Bathers. "With Bathers, it's the same person, myself, cloned three times. But it's almost like three giants in a landscape, looking down and over a landscape that's kind of apocalyptic."

Your work began to change around 2008, with Bathers for example. The works were less confrontational and became more painterly.

"I don't really know how it started off. I think it was because I was tired of the face and began thinking of using the entire figure and reconstructing classical painting. There was always a figure and the language of the gesture. I remember looking a lot at Caravaggio, as well as paintings of bathers, a common theme for centuries. And I thought, 'Let's see what I can do with that.' With Bathers, it's the same person, myself, cloned three times. But it's almost like three giants in a landscape, looking down and over a landscape that's kind of apocalyptic. I think it harks back to when I visited the Walker Art Gallery as a child. There were paintings by an 18th-century painter, John Martin, who painted apocalyptic scenes, skies on fire, volcanoes, raging storms at sea, and tiny, tiny people tumbling from cliffs. It also struck me that the three large figures were almost like Three Fates, watching, gazing down on the destruction as the world burned and tiny figures plummeted to their doom."

Lamia, Desert (Lilith Series): "It was about moving away from the male gaze, challenging the ways that women had been perceived, and represented, taking control of the narrative."

Around the same time, you also made Lilith and Lamia and Muse, and in the latter, there was a nod to Gustav Klimt. You were not only tapping into art history during this period, but also mythology, sometimes through art history and how women have been portrayed in it.

"I was always very interested in how women painters, particularly in 70s and 80s, painted the female nude, themselves or others. It was about moving away from the male gaze, challenging the ways that women had been perceived, and represented, taking control of the narrative. I was taking control of my personal narrative, but I was also referring to the larger context, historical and social. What do the poses and gestures of women in classical painting mean? Most are quite ridiculous, theatrical and bombastic. But they're languages that are formalized and embedded in visual culture, and mostly that culture is male. I wanted to play with these things, to use exaggeration and masquerade to shows things from the perspective of the female gaze."

I was struck at the time by the many layers in your work. So much of the staged photography that emerged at the time seemed to me, to be what would today be described as Instagram inspiration, take an image and simply reuse it without actually adding anything. But your approach was very, very different and has remained so.

"I work intuitively. I have a stylus and a tablet, but often use a mouse because it's annoying, so it forces me to make weird gestures. When I'm working on an image, it's more like drawing them because I use my entire hand to get the mouse to do what I want and it's kind of clumsy. And I like that clumsiness because it adds to that sense of not quite being in control. I take bits of images, and I control that side. But then when I get to the actual work, it's almost like a battle. I can get very frustrated but that's part of the process because the images have to mean something, not just look good. They need to challenge your brain. There's something in your brain that has to be almost forcibly extracted in order to arrive at an image that has some kind of power, to communicate with someone else, and that's the bottom line."

Those who followed you during those years were quite surprised when you then presented the series Constructed Landscapes. Why did you turn away from the figure?

Pale Forest (from Series "Constructed Landscapes"): "When I revisited where I grew up in the UK, I thought, 'Why not try to create my own landscape.' So that's what I did, stitching together disparate images taken over the years, constructing a topography that condenses time and place."

"I simply reached a point where I wanted to create more abstract spaces in which the figure was a blurry presence or not present at all. I started photographing around the area where I had grown up. I would go back to the same trees, a clutch of pines I've always loved since I was a kid and photograph them obsessively over and over. Then I collaged that footage with images that I had taken in South Africa. It was a way to piece my own story together, but without my presence in the images. I used material I shot in Austria, too. When I met my birth father, he took me up on the mountains, covered in snow. We looked down over the valley and he threw out his arms very melodramatically, and said, 'All this is yours. Du bist eine Tirolerin.' I nearly laughed because it was just so hammy and stupid. But when I revisited where I grew up in the UK, I thought, 'Why not try to create my own landscape.' So that's what I did, stitching together disparate images taken over the years, constructing a topography that condenses time and place."

They're strange landscapes, haunting, not decorative.

"I've lived in the Netherlands for a long time, and sometimes I go for walks in an area of dunes. The country was occupied during WWII, and there are a lot of bunkers, even bunkers built by the Stedelijk Museum where they kept their art collection during the occupation. During one walk, I came across a sign saying that this was the site of a mass grave, where resistance members during wartime had been buried. I even found an old bullet casing. At some point, I began thinking about landscape and the traces we leave. I started a kind of thought experiment, trying to see things from the perspective of the landscape, of the pine trees, the grains of sand, the insects, and the bodies that had once been buried there, imagining a dialogue between all those things. Between nature and humans. A reminder that landscape has always been a space moulded by humans, that we not only exploit nature for profit, but to tell stories about cultural identities, or obsessions, or even evoke a sense of awe or fear. I wanted to tap into that."

There was another turning point in 2011, with Woman with Apples. For the first time, you didn't use yourself as a model.

"The model was someone who liked my art and asked me to take her portrait. I did the portrait as a commission. I wanted to try doing something with interiors, with a reference to still life. I decided to use fruit, not nice fruit, but old apples, bruised and marked. I was referencing the Golden Age in Dutch painting, when a still life in the home marked status and wealth, but of course the fruit in the bowl is beginning to spoil, which makes a jab at the colonial era. I collaged the images together, creating different layers, different kinds of textures, and a sort of indeterminate space where you see a woman. Her presence is also a nod to still life, almost as though she is one of the inanimate objects. That image led me to the following series."

You mean The Blue House?

The Empty House (Blue Shadows): "The Blue House series was inspired by John Singer Sargent's painting, 'The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit'."

"The Blue House series was inspired by John Singer Sargent's painting, 'The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit'. It's a very strange portrait because all four girls appear to be captured in an enclosed space, like specimens of moths or butterflies. Alive and yet not quite. As if they are simply objects, almost like a still life. I was intrigued. I looked at that painting a lot--in books and online, I've never seen it in real life--and felt I understood the dynamics of the scene, that the girls were in a kind of fugue state, or suspended in time. When I started work on my series, I soon realized I needed to stay behind the camera and use a model, a stand-in, so I could stage the images effectively. A friend recommended someone, a dancer, who was interested in the project and helped me create the feel and energy I was looking for. Then, a year or so later, it was interesting, because when the images were shown at AIPAD, a guy in his 30s came to the stand and looked at them intently. He was ex-military and had been badly burned while serving overseas. He had been brought up by his mother, didn't know his father and he recognized the sense of disconnection the images convey. He was also a photographer. We spoke for about an hour and a half about photography and what creativity is, and it made me realize that my work had a function beyond my own aesthetic, that it actually does connect."

There was also an interesting project you did in 2016, Opera Holland Park.

"The opera company wanted work that was figurative but not really photographic and not really painterly. My name was suggested to them. I used my archival images and changed and adapted them to the specifications of the brief. It was like creating illustrations, less complicated, because while there was a story, it wasn't my story."

What have you been working on recently?

"I'm continuing with the landscapes, and I'm also experimenting with photographing water. I've been looking at Monet's work, and his colors and how he uses light. I'm trying to focus on what water might mean, its symbolic embodying of the subconscious. There was always an abstract side to my work and with the recent images, I'm concentrating on the layering and want to see how far I can take that. I'd like to make a more hybrid series that explores the disjointed quality of how we live now--we're all addicted to our phones; and there's a disconnect between our lived reality and this digital reality. I'd like to get deeper into that, and experiment with printing images on a different carrier, perhaps on transparent paper or even fabric, and creating layers, carefully placed in the frame."

Do experimentation and new working methods keep you on your toes regarding the emotional content of the work?

"I think about those things while I'm making the work. Some of the works start off really small on my phone. I give myself a challenge, 10 minutes to create an image with some kind of emotional charge. And if it fails, it fails. It's a kind of try/fail cycle, and it always brings interesting results."

Looking back, do you think art helped you get through the process of coming to terms with your past and building your own identity?

"It did to some extent, but I could have done it in some other way, because I don't think that the art itself was therapeutic. It was more a way to create a channel, find my own language, and to communicate. It's about communication and tapping into emotions and experiences that many of us share. I used my vulnerabilities, and I was quite open about them. I exploited them and put them out there for someone else to find. An invitation for others to engage with a sense of vulnerability and to look into themselves and beyond. That's what it's always about."

To see and to order photographs by Lisa Holden, go here: https://iphotocentral.com/common/result.php/256/Lisa+Holden/0/0/3.

To order one of her currently available photobooks, go here: https://iphotocentral.com/common/result.php/36/KKK/Lisa+Holden/0.

To see our Special Exhibit: Lisa Holden: New Work--Constructed Landscapes and Haunted Portraits, go here: https://iphotocentral.com/showcase/showcase-view.php/24/0/243/1/16/0.

And here for the Special Exhibit: Contemporary Photography of Lisa Holden: Victorian Dreamscapes and New Technology: https://iphotocentral.com/showcase/showcase-view.php/24/0/81/1/16/0.

For institutions interested in her work, please call Alex Novak at 1-215-516-6962.

Michael Diemar is editor-in-chief of The Classic, a print and digital magazine about classic photography. In August 2025, he cofounded Vintage Photo Fairs Europe, an organization focused on promoting independent tabletop fairs in Europe and spreading knowledge about classic photography in general. He is a long-time writer about the photography scene, writing extensively for several Scandinavian photography publications, as well as for the E-Photo Newsletter and I Photo Central.

24.39 Classic Photography Fair Attracts Vintage Photography Buyers

Lisa Holden: A More Complex Feminist Path, Exploring Emotion, Identity and Vulnerability

Share This