Photo London Moves to a Redeveloped Olympia in 2026

FOMU – Fotomuseum Antwerp: An Interview with Tamara Berghmans, Curator of the Collections Department

Summer Sale of over 4,000 Photographs on I Photo Central at 30% Discount

Italy Reduces VAT on Art and Photography Sales to 5%

Human Rights Lawyer to Defend Artist Gao Zhen, as China Holds the Artist's 7-Year-Old American Son

Some Recommended Vendors that We Have Worked with.

Tamara Berghmans (Photo Courtesy of Thomas Sweertvaegher)

On October 23, FOMU, Fotomuseum Antwerp will open the exhibition "Early Gaze; Unseen Photography of the 19th Century". Tamara Berghmans, Curator of the Collections Department explains, "The last exhibition FOMU did on the subject was in 1989. Since then, more research has been done, more material has come to light; and not only that, the discourse has changed, the way we look at the period and the various ways photography was used. Sure, the exhibition includes masterpieces from the period, but also problematic images, such as medical and colonial images."

Belgium has two large national language groups, French and Flemish, which has resulted in two national photography museums, Musée de la Photographie in Charleroi and FOMU in Antwerp. Just like the museum in Charleroi, FOMU has a complex history. The story begins in 1965 when Karel Sano, department manager at Gevaert Photoproduction, and Piet Baudouin, a curator at the Sterckshof Museum of Decorative Arts in Deurne presented an exhibition entitled "125 Years of Photography". The exhibition was supported by the then recently merged Agfa–Gevaert company and was hugely successful. The company then transferred the exhibition loans to the province of Antwerp, whereupon a plan was hatched to open a photography museum. A working committee under the name of Photo & Film was established, under the leadership of Karel Sano, then Laurent Roosens, and in 1973 the task was handed over to the scientific department at the Sterckshof Museum.

FOMU, exterior, photographed during an exhibition with Cindy Sherman. FOMU Antwerp © Robin Joris Dullers / FOMU Antwerp

The collection grew under the leadership of historians Roger Coenen and Pool Andries, to the extent that it was too large for the museum to store. As a consequence, in late 1980, the collection was moved to a former office building on Karel Oomstraat and was renamed the Museum of Photography. The museum found its present home in 1986, in a former warehouse, known as Pakhuis Vlaanderen on Waalsekaai, and a new wing was added to the building. A further renovation followed, and in 2004 the museum reopened with 1400 square meters of exhibition space, two cinema theaters and workshops.

Tamara Berghmans has been Curator of the Collections Department since 2013. I started by asking her what drew her to photography in the first place.

"I come from a working-class background and I was the first in my family to study at university. I decided to study art history as it seemed interesting and I didn't know anything about it. In my third year at Vrije Universitet in Brussels, there was a series of lectures on the history of photography. It was the first time I heard anyone talking about photography as art, about the medium's complex relationship with reality and all the different interpretations of reality. It opened up so many questions about what we see, what we don't see and the ways in which photographers dealt with that really gripped me.

"But here was another reason why I decided to focus on photography from then on. I saw my fellow students working on Rubens, Old Masters and leading names of contemporary art, basically doing the same research. I realized that there were so many areas of Belgian photography that hadn't been researched, that it would be possible for me to do basic, original research, whether it was in archives or talking to photographers. It was such an interesting prospect, that there was a great field to explore."

How did you progress in your studies?

"For my Master's degree, I researched and wrote about a group of Pictorialist works that had been acquired by the Belgian government in 1898. For my PhD, I worked on the first truly modern art photography movement in Belgium, the subjective photographers who had been influenced by Otto Steinert in Germany. In Belgium, Pictorialism lasted a lot longer than in other countries, with Léonard Misonne being one of the leading practitioners. He died quite late in 1943, and there were a lot of amateur Pictorialists who carried on working in that style. The first break came in the 1950s with the subjective photographers who started their own modern movement. The great thing for me was that so many of them were still alive. They were in their 80s and 90s, and they still had their archives. As they were getting on in years, there was a small window for me to talk to them."

The history of European fine art is long and complex. Do you feel that the study of Belgian fine art history has overshadowed that of Belgian photography?

"Generally, the history of photography is still such a young discipline even though there are more and more researchers. But you might have a point. When I finalized my PhD in 2008, I was the very first in Belgium to have a PhD in History of Art on the topic of photography. Today, almost 20 years later, photography is taken more seriously at university level."

Having finished your studies, how did you start your career?

"While I was doing my PhD in Brussels, I also took a course in the Netherlands, at Leiden University. The one-year Master's program was called Photographic Studies and was a collaboration between the university and the Academy in The Hague, and you could combine theory with the practice of making exhibitions. I took the course because I felt quite alone in Brussels, being the only one working on photography. I felt a need to be more in contact with other researchers and other people working on photography.

"The Photographic Department of the Leiden University's Print Room included the dummies for Ed van der Elsken's book "Love on the Left Bank" and I fell deeply, deeply in love with that book. I decided to do my internship at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where they have a large group of vintage prints of Ed van der Elsken, enabling me to research "Love on the Left Bank". The contacts I made in the Netherlands were very important because after that, I had the opportunity to be assistant curator at the Stedelijk Museum. Following that, I applied for the Manfred and Hanna Heiting scholarship at the Rijksmuseum, where I did research on Sanne Sanne's Maquette for "Diary of an Erotomaniac", in collaboration with Hans Rooseboom and Mattie Boom, which resulted in a book published in 2009. After that, I lectured at Vrije Universiteit Brussel for two years. Luckily for me, there was an opening at FOMU in 2010 and in 2013, I became curator in the collections department."

The collection, or rather collections that you were put in charge of are spectacular.

"Indeed. It started in 1965 with the exhibition "125 Years of Photography at Sterckshof", a museum for decorative arts. Many of the loans came from the recently merged Agfa-Gevaert company and were donated afterward to form a founding collection at a new film and photography department at the museum. In 1966, the archive and library of the Association belge de la Photographie were transferred to the museum. The library contained some very important 19th and early 20th-century literature on photography. There were also works by Pierre Dubreuil. In 1966, Agfa-Gevaert donated the photo archive of the now defunct Publication Department to FOMU. It included pictures that had been published in their magazine, Fotorama, published between 1952 and 1958 in different languages. There were images by Brassaï, Robert Doisneau, and many others."

What acquisitions followed?

"In 1973, there was another important acquisition, of historical photographic equipment from the collection of Michel Auer of Geneva. It formed the basis of our camera collection. Today we have roughly 23,000 cameras and it's one of the most important collections in Europe. It was added to in 2005, when the former Agfa-Photo-Historama deposited their cameras with us. Their images were purchased that same year by the Ludwig Museum in Cologne.

"In 1978, we acquired a part of the Fritz Grüber collection, which included images by Man Ray, Ansel Adams, William Klein, Edward Weston, Irving Penn, August Sander and others, the classic canon. After that, acquisitions were often made when the museum presented exhibitions. In 1990, Agfa-Gevaert sponsored the museum which enabled the acquisition of important American post-war photography, such as that by Minor White, Aaron Siskind, Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Stephen Shore and others. In 1992, with funding from the Belgian National Lottery, we were able to supplement our holdings of Belgian 19th-century photography, by L.P.T. Dubois de Nehaut, Guillaume Claine, Edmond Fierlants and others."

In 2015, FOMU acquired the Agfa-Gevaert company archive.

"It was a donation by the company and the archive is absolutely huge. In terms of storage, it takes up more than 400 linear meters of shelving and includes photographic papers, packaging, promotion materials, construction plans, correspondence and much else. The archive is very important because there aren"t that many photo industry archives that are complete and this one is. In addition, we have around 40 other archives, mostly Belgian photographers, and altogether there are about four million objects in the collection. We have reached the point where we had to stop accepting archives as we simply don't have the storage space, the budget and the staff to deal with them, a problem that many museums have."

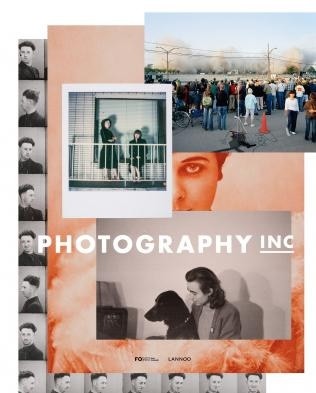

A few years after, you curated "Photography Inc.--From Luxury to Mass Medium", presented in 2015-2016.

Photography Inc. From Luxury to Mass Medium, presented in 2015 – 2016. Tamara Berghmans (ed.), Photography Inc. From Luxury Product to Mass Medium, Lannoo/FOMU 2015.

"Photography Inc. was a collection presentation but with a focus. It was at the time when we were preparing to receive the Agfa-Gevaert archive. A lot of the time, people just look at the images. What was interesting for me was the relationship with the photo industry, because the industry is so important in the history of photography. Why are people working hard to improve the technology? Who is the audience? Why are photographers doing something? It was an opportunity to look at the collection in a different way and also talk about the technological history. What was the impact, not only historically, but also today of the industry?

"We used to get a lot of criticisms from the older generation, that we weren't showing enough of the cameras in the collection. In the past we used to display them without context, but this had no added value for FOMU anymore. After the necessary research, we were able to present them with context in Photography Inc. This was a good way of showing a lot of them and also provide context, why the cameras were constructed that way, what kind of images were made, who the photographers were and why the images were made. I was pleased to note that the younger generation--now that everything is digital--was fascinated by the analog materials."

Has the acquisition policy changed since you up the post in 2013?

"Over the past decade, the approach to collecting, along with society itself, has radically changed. I don't make the acquisition decisions on my own. We work as a team at FOMU. Back in 2013, our budget was quite small. I'm not saying that our budget is now huge, but it became bigger after 2020 when FOMU became part of the city of Antwerp. With limited resources, we have had to be clever and focused when it comes to acquisitions. In the 80s and 90s, works were acquired with no specific criteria or goals. Acquisitions also tended to follow the exhibition program as it's easier to get a better deal and donations when you organize an exhibition.

"During my first 10 years at the museum, a lot of the works that entered the collection were by Belgian photographers. It's part of our mission. In the last few years, we felt we needed to define our criteria with more precision because if you look at all the photo museums in Europe, the collections are very similar. They all have Diane Arbus and Robert Frank. And I think it's necessary to diversify, to choose with a different mindset because we can't just keep on hoarding like we did before. And there's another aspect to this. Our funding is not private, it's public, that is, it comes from the community and it means we have a responsibility to the community."

How has that been reflected in the exhibition program?

Re-collect, at FOMU, 07/05-07/11/2021 © We Document Art / FOMU Antwerp. Re-collect, presented in 2021, was a kind of associative walk through the works that had been acquired in the previous 10 years.

"We did an exhibition in 2021, "Re-collect", a kind of associative walk through the works that had been acquired in the previous 10 years. During the preparations for Re-collect not only were the seeds sewn for a new way to present the collection, but we also took a hard look at FOMU's acquisition policy. This scrutiny revealed three important focal points over the past ten years: a focus on Belgian photography, on international photography of social relevance and a clear connection with the museum's exhibition policy. What also became apparent was that between 2010 and 2020 FOMU had acquired little work by artists of color and women photographers. As in many other European museums, female makers account for a mere 10% share of the FOMU collection. A great deal of work remains to be done to achieve a diversified acquisition policy that is balanced in terms of gender, color and background. There was plainly a need for a more defined collection profile that set out clear choices. We wrote a new policy plan for the next five years, criteria that would be applied to the whole museum, making it multi-voiced. The sharper collection profile that we have since drawn up focuses on autonomous artistic photography in all its manifestations. At the same time, we collect photographic heritage, which encompasses the history and development of photography in Belgium, and we position this within international practices."

In 2024, FOMU presented an exhibition on Gevaert papers. It coincided with the launch of the Online Databank of Gevaert Photo Paper, the result of a five-year research project.

"The Agfa-Gevaert company archives included 377 types of paper and 1,300 packages of paper. We did a thorough inventory of this material, in collaboration with conservator Paul Messier, who has researched photo papers in-depth and has assembled a vast collection of papers. Having instigated this project, we decided to create a small exhibition and video, making connections between Gevaert papers and practitioners. We acquired works by James Barnor, who was a representative of Agfa-Gevaert in Ghana, as well as works by Alison Rossiter, a contemporary artist who works with outdated paper stock, in this case, works created on Gevaluxe Velours paper that had been given to her by Belgian artist Pierre Cordier. The exhibition also explored the qualities of the different papers, texture, color, thickness etc. and how they were packaged and promoted."

The darkest chapter in Belgian history concerns Leopold II, the second king of Belgium, and the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State, his own private colony. Estimates vary but millions were killed and many more were mutilated under his brutal regime. How has FOMU dealt with the colonial era as far as exhibitions are concerned? And is it dealt with in the upcoming exhibition on Belgian 19th-century photography?

"In 2022 – 2023, we presented New Perspectives on Photographic History of Colonial Congo, researched and curated by Sandrine Colard, historian of African, modern and contemporary arts, as well as a historian of photography. It tackled the multilayered history of photography in the Belgian Congo, with works ranging from propaganda images to amateur and studio photography from the period 1882-1960. We also published a book that won the 2023 Paris Photo-Aperture PhotoBook Juror's Special Mention. We are also dealing with the colonial era in our upcoming exhibition on 19th-century Belgian photography. We have decided to show images that were made at three World Fairs here in Antwerp, in 1885, 1894 and 1897. The images are of "human zoos", Congolese people that were exhibited just like animals in a zoo. For many visitors to those fairs, it was the first time they saw Congolese people. The images were used as propaganda. All colonial photographs are problematic but it is important to show them and give context, examining the layers of power and oppression, discussing agency and missing perspectives. In the past, exhibitions on 19th-century photography have often been about the beauty of the images, the photographers, without examining the wider context. The last big show on Belgian and Dutch photography was in 1989. The research that was done at the time is very important of course but since then, new material has been found, new research has been done and our way of thinking has changed. We can't look at the same topics with the same old-fashioned gaze. We have a contemporary audience. It's not always possible to find the images we would like to show and then questions arise. Are they not there because they were not made? If they were made, were they not collected or did they simply disappear?"

I get the impression that there will be a lot of unexpected images in the exhibition.

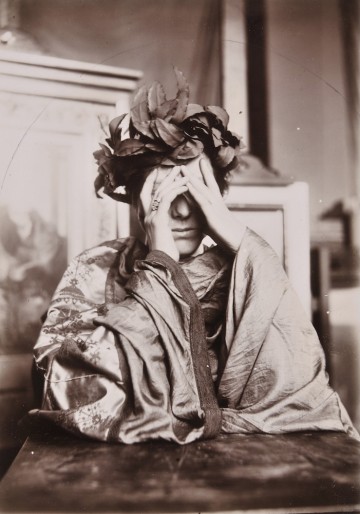

Fernand Khnopff, Portrait of Marguerite Khnopff, ca. 1890, gelatin printing-out paper, Collection FOMU. One of the 500 images and objects going into the exhibition "Early Gaze; Unseen Photography of the 19th Century".

"It's a very ambitious show, with altogether 500 objects. About half of it comes from the FOMU collection and the other half comes from other collections, including Collection Philippe Janssens, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, Société française de Photographie in Paris, Royal Library of Belgium, the State Archives of Belgium, City Museum of Ghent, the Africamuseum in Tervuren, Musée de la Photographie in Charleroi and Musée de la vie Wallone in Liège.

We started working on it five years ago, and we will show it in two big exhibition halls. Sure, there are many masterpieces in it but there are also many difficult images, not just colonial images but also medical images, created for medical doctors or researchers. In most cases, the people in the photographs never gave their consent to be photographed so how do we deal with this today? As with everything we show, we ask ourselves, what is the ethical position of the photographer? How can we show specific kinds of work? What context is needed? These are important questions."

How did you go about researching and selecting material for the exhibition?

"There were only a few real experts on the subject in Belgium, like Steven F. Joseph, Pool Andries and Herman Van Goethem. We wanted to do the research ourselves in order to become experts in the field, so this exhibition is not like an end point, more like a beginning for us in 19th-century photography. We are 15 people in the collection department, and leading up to the exhibition, we are doing a six-week course on the determination of photo historical techniques and processes, just to make sure that everybody knows what kind of material they're working with, and that includes the people from the administration department and the framer.

"In the last three years, we have visited a lot of archives and collections, which resulted in the discovery of some remarkable crime scene photographs. We found two police mug shots, taken in 1843 by Brand frères, the first ones taken in Europe I believe. Steven found the glass plate negatives of Leopold II's by Dubois de Henault at the ST Janshospitaal in Bruges. They will also be on show. as well as the salt prints that he made from them."

Steven F. Joseph has also been involved in the Directory of Belgian Photographers, now available online in a beta version.

"It's a revised and expanded version of the Directory of Photographers in Belgium 1839-1905 by Steven F. Joseph, Tristan Schwilden and Marie-Christine Claes, published in two volumes by FOMU in 1997. It is now extended until 1914 and the outbreak of WWI. Nearly 3,200 listings have been added. It has some 8,600 entries, including 350 cross-references, covering professional and amateur photographers as well as firms and individuals active in connected trades."

On the subject of research projects, can you tell me about Daguerreobase, the Daguerreotype project?

"Daguerreobase was a project that was started in 2012, with FOMU as coordinators. It was a database that was funded by the European Commission. The purpose was to document all European daguerreotype plates. There was a consortium of 18 partners from 13 different countries, where every partner was responsible for contacting collections in their country, not only public collections but also private, which was quite hard because many private collectors didn't want to reveal what they have. Images and data were collected and stored in the database. The project ran for three years, but the website has been online since 2015. It hasn't been updated the last few years, but the detailed information can be still accessed online"

In 2019, you published your book "Photobook Belge", and it was accompanied by an exhibition at FOMU.

"My love for photobooks started with the Ed van der Elsken book that I mentioned. In the early 2000s, all those large books on photo books began to appear. I thought "Great! But when will something be published on Belgian photobooks?" I discussed it with the team and we realized we would have to do it ourselves. And why not? Because we have a huge photobook collection, including more than 30,000 volumes, probably the most important of its kind. I didn't make the book on my own but worked with different writers and experts on different topics. It was also an opportunity to acquire more books and give a boost to our library, making people aware of it. For photographers in Belgium, it was important that this book was produced. Still, I could only include 250 books and you always have to kill your darlings. But I have the feeling that this was the first volume. In a few years, there should probably be another book."

Grace Ndiritu Reimagines the FOMU Collection, at FOMU, 2/17/2023 – 1/7/2024 © We Document Art / FOMU Antwerp.

In 2023 – 2024, FOMU presented "Grace Ndiritu Reimagines the FOMU Collection".

"Grace Ndiritu is a British-Kenyan artist and we invited her to reinterpret the collection. She saw shamanism as a means to reactivate "the dying art museum" as she called it, and she created a refuge, a space for slowing down and reflection, inviting visitors to see with an open mind, make intuitive connections and abandon rational thought processes. We have continued working with this concept and we are currently showing "No Longer Not Yet – Katja Mater and the FOMU Collection". It"s the third such exhibition at FOMU, and they represent an atypical way of working with images. And for us in the museum, a lot of emotions come to the surface because you're confronted with yourself and with your sometimes dogmatic ways of working. 'Where are our boundaries? How far can we let somebody go with the collection and with our ways of working with a collection?' It's very interesting and challenging."

A new exhibition concept for the museum and one that led to several changes I believe?

"Instead of just showing these artists and photographers, we ask them to play a bigger role in the museum, to share the power and let them make decisions. As a curator, we take a step back. They control the discourse of what they will be showing. On the advice of the guest curator, the museum can acquire work for purposes of the show. It's a very interesting way of working, and also a very intense way of working because we as museum people have a specific way of thinking and working. while they approach the relevant questions in a very different way, challenging and questioning what we do.

Have all the staff come on board for this way of working?

"As a museum we are responsible for adjusting the canon and offering the audience a broader, multi-voiced perspective. For this it is necessary to let go of control and to share responsibilities. We have to consciously go out looking for other artists and networks, refresh and up-skill our expertise and continue to scrutinize the collection. The ultimate goal is to create a place where everyone can feel at home and where connections are created between art, culture and society. By not always choosing the easiest path, but instead opting for the most fascinating, FOMU can constantly reinvent itself and retain its relevance for the future.

"We're still not there. It's still a work in progress. That's also the case with the collection, how it is described in the inventory, and the words that are used. Right now, we are also working on a big project on language and image sensitivity in the collection and in the museum. How are we going to deal with old descriptions of images and the words that are used? How do we deal with offensive images in our database? This is something that every museum is dealing with, and what we are trying to do is to work with as much participation as possible."

"Early Gaze: Unseen Photography of the 19th Century" runs from October 23, 2025 to March 1 2026.

Michael Diemar is a London-based collector and consultant. He is also editor-in-chief of The Classic, a magazine about classic photography. He is a long-time writer about the photography scene, writing extensively for several Scandinavian photography publications, as well as for the E-Photo Newsletter and I Photo Central.

Photo London Moves to a Redeveloped Olympia in 2026

FOMU – Fotomuseum Antwerp: An Interview with Tamara Berghmans, Curator of the Collections Department

Summer Sale of over 4,000 Photographs on I Photo Central at 30% Discount

Italy Reduces VAT on Art and Photography Sales to 5%

Human Rights Lawyer to Defend Artist Gao Zhen, as China Holds the Artist's 7-Year-Old American Son

Some Recommended Vendors that We Have Worked with.

Share This