Bassenge Holds Auction of Chinese Photos, 1890s-1950s, Plus Multi-Owner Sale in Berlin on June 4th

London Photograph Fair Changes Hands Again

Over 300 New Items Posted up for Sale on I Photo Central Web Site in Just the Last Three Months

Photo Book Reviews: America, London and Photographers in View

AMERICA IN VIEW: LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHY 1865 TO NOW. Published by the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Approximately 70 color plates; 126 pages; hardbound; ISBN No. 978-0-985-61890-2. Information and ordering: http://www.risdmuseum.org.

Capturing a tradition of landscape photography as sweeping as the land itself, this beautifully bound and printed catalog conveys the solid pedigree of the Rhode Island School of Design through a display inspired by a gift to the RISD Museum of 71 landscape photos by the late Joe Deal and his wife, Betsy Ruppa. Context is provided by three illuminating essays from Deborah Bright, Jan Howard and Douglas Nickel, but the photography speaks for itself strongly enough.

Beginning with 19th-century views of dust-swept railroad tracks somewhere in the southwest by A.J. Russell, the American landscape lens takes in the elemental monumentality of nature: sublimely perched boulders in Arizona, pristine junctions of the Colorado river and, by 1930, the dunes of Death Valley, as scanned by Willard Van Dyke. These near-abstractions communicate spiritual breadth and the forbidding sense of T.S. Eliot's Waste Land all at once, just as Walker Evans' and Brett Weston's urban landscapes--the modest sprawl of homes in Easton, PA, or the flow of traffic past a vintage Coca-Cola sign astride the Brooklyn Bridge--are simultaneous symbols of American vitality and choking growth.

By the mid-1940s, American landscape could, and did, contain multitudes of graphic possibility, whether the allover pinpoint scrubland of Arizona from Fredrick Sommer's point of view or the rocky California cliffs and ponds, darkly atmospheric, as seen by the Westons (Edward and Brett). Ralston Crawford notes the incursion of high-tension electrical wires across flatland, while Harry Callahan scales his wife, Eleanor, against the winter bareness of tree trunks in a Chicago park, and Aaron Siskind seeks the expressionistic grail of closely read textures in the rocky crevices of Martha's Vineyard.

By the '80s and '90s and into this century, of course, the modernist eye has seen and documented so much that the post-modern sensibility of Stephen Shore finds visual complexity and sun-blasted color in the random juxtaposition of Idaho potato commerce and a cheap motel facade. David Hanson and Terry Evans look from on high, judgingly, at the patterns of coal strip mines, waste ponds and terraced plowings. To Linda Connor or Sally Mann, the dark, scattered stones of Hawaii's Kau Desert or Antietam's ghostly wilderness are like alien ruins, so subjectified by their minimalist artistry that the essence of American landscape seems truly transformed.

As Deborah Bright's essay puts it, "If there is an overarching emotional and dramatic tension in the American Landscape Story in this exhibition, it lies along an axis of sublimity and pathos...a feeling of being overwhelmed by the magnitude of an experience [and] a feeling of sorrow, empathy and tenderness for the loss of something that was once grand and noble." Indeed, RISD's rigor and its unsentimental approach to this familiar subject matter is to highlight the tensions as they define the pure expression of American landscape and the attitudes behind it, from the early need to document the continental vastness to the later emphasis on critical observation. These images, like the land, are marked and unmarked--by human presence and absence, by time and industry, and ultimately by the artist's knowing eye.

ANOTHER LONDON: INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHERS CAPTURE CITY LIFE 1930-1980. Edited by Helen Delaney and Simon Baker. Tate Publishing, accompanying a 2012 exhibition of the same name at the Tate Britain Gallery, London. Approximately 100 black-and-white prints; 144 pages; hardbound; ISBN No. 978-1-84976-025-6; information and ordering: http://www.tate.org.uk/publishing.

These photographs of London--its archetypal imagery and the individuality of street life captured in decisive moments--are from the collection donated to Tate Britain by Eric and Louise Franck, and the exhibit is a tour de force of great names in 20th-century photography. From Eve Arnold and Bill Brandt to Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bruce Davidson, Elliott Erwitt, Robert Frank, E.O. Hoppe, Inge Morath, Irving Penn and others, the range of vision is wide but the subject is wonderfully narrow: London as a state of mind and a paragon of urban culture. The damp mist, the Beefeaters, the bridges and railways, the embankments and the omnipresent sense of a city as old as time: such are the touchstones of these black-and-white moments, but each is wonderfully unique.

Jacques-Henri Lartigue sets the scene potently in 1926, with a near-panoramic vision of "Bibi in London," with a dark mass of pedestrians to the right of the wide frame and a woman walking toward us, set apart, in the long coat and flapper cloche of a 1920s dream, while the double-decker buses and vintage traffic eat up most of the scene; it is urban bustle as only London can portray it. From there, the foggy backdrops of Parliament and the Thames are the atmospheric context for ceremonial majesty--the Changing of the Guards--or random sublimity: a pigeon calmly perched on London Bridge, by Hoppe. Flowers in Picadilly, or the hustle of the Portobello Road Market are brusquely picturesque, while Brandt's spooky image of a tatooist's window in Waterloo Road leaves us to wonder if Mr. Hyde is lurking in that shadow.

Brandt captures London about as well as can be in this fine collection. He looks for details and frames them in architectural poise that renders them endlessly interesting: a housewife in 1937, scrubbing her hands amid her housework, is offset by the old brick of her London home; an early morning still life of milk bottles and newspapers on a doorstep is sheltered by stone corners and the lower end of a round pillar. But Brandt, for all his masterly chiaroscuro, is hardly alone in thrall to classic London: Hans Casparius captures boys roughhousing in Trafalgar Square, a vibrant image of 1930s everyday joyousness. As for Cartier-Bresson, he locates spectators waiting for the coronation parade of George VI in 1937, in top hats and newsboy caps, spectacles and woolen wraps; while Herbert List notes the reflective puddles in Hyde Park as passers-by hurry on.

As the decades hurry on, the images grow cluttered with fresh references and the turmoil of time and changes. Sergio Larrain's 1959 shot of pedestrians, in close foreground, mid- and far background, is a fragmented canvas of post-war anxiety, as is Bruce Davidson's high-angle shot of a Blitz-bombed-out car park in 1960. The '60s, of course, change everything, as London swings into its gritty, cheery cultural chaos, and Dorothy Bohm's camera brings us the flea markets of Covent Garden and Petticoat Lane. By the mid-'70s, Karen Knorr and Olivier Richon capture the no-future, high-contrast, leather and dog-collar nihilism of punk, while other photographers capture the mixture of races and styles that affirm London as the world's epicenter. As the '80s dawn, Elliott Erwitt's image of a downcast Hyde Park picketer, forlornly holding his sign--"The End Is At Hand"-- assures us that, barring apocalypse now, there'll always be an England.

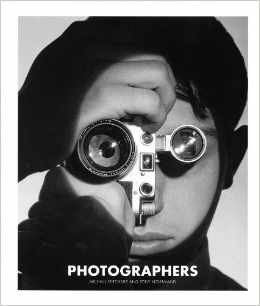

PHOTOGRAPHERS. By Michael Pritchard and Tony Nourmand. Reel Art Press, London, UK. 287 pages; hardbound; approximately 200 black-and-white and color plates; ISBN No. 978-0-9566487-7-8; information: http://www.reelartpress.com.

This handsome volume stands well apart from most coffee-table photography books, since its focus is not so much the subject of well-known photographers but the photographers themselves. Co-author Pritchard, Director-General of the Royal Photographic Society in Bath, UK, and Reel Art Press editor Nourmand have done an excellent job assembling and contexualizing this generous collection of vibrant images that pay homage to the makers of photography in all its forms, from low to high. Pritchard doesn't overstate the obvious; his concise introduction gives an authoritative sense of how the medium has changed, and how the photographer's role and image have evolved at the same time. He notes how the innovations of smaller cameras and snap-shooting expanded the notion of who could claim to be a photographer, along with the expansion of world markets for photography, the rise of cinema, celebrity, mass culture and media.

In short, photography is, to restate the obvious, the most democratically accessible form of image- and art-making, but its greatest practitioners remain relatively, and ironically, unknown and largely unseen. Thus, Bert Hardy's crisp 1953 image of actress Ingrid Bergman, in profile, aiming a camera during a break from filming, sharply comments on the nature of photographic fame, as do the innumerable shots of anonymous photographers gathered, flashbulbs popping, at major events. So it's nice to see fine self-portraits of photographers we love, such as Robert Doisneau, an intense, detective-like presence behind his Rolleiflex; or Alfred Eisenstadt in 1933, dour, balding and cerebral, as if his thought processes were too busy to maintain a hairline; or Gordon Parks in 1948, his darkly leonine looks more familiar to us thanks to the publicity he won as one of America's premier black artists.

If anything, the crafty, technically preoccupied--shall we say nerdy--photographer is rarely a subject for the camera. If they come as picaresquely unkempt and vaguely sinister as, say, Weegee, they don't exude much glamor; and so it goes when they are buttoned-up and businesslike, which is much of the time. But more than a few of them had high style: Cecil Beaton, posing Andy Warhol and a couple of Warhol's Factory denizens, is as colorful and dashing, in his eccentric formality, as any of his subjects. And Margaret Bourke-White, her blonde hair whipping in the wind as she stands, Fairchild K-20 aerial camera in hand, before a US Flying Fortress bomber during a World War II assignment in Tunis, is the very image of the intrepid romantic.

But there are just as many images of photographers taking pictures as there are self-portraits of the artists. And these you-are-there tableaux bring us into the realm of the photographic mystique and the obsessional nature of freezing a moment in time. The mirror image of Ed Feingersh snapping away as a voluptuous Marilyn Monroe is fitted for a showgirl costume in 1955 is a study in the rhythm and chance of getting the shot. Feingersh shoots as a second camera hangs from his wrist, his concentration all but walling him off from the moment itself, as Monroe preens, impossibly beautiful, and her handlers hover. There he is: the photographer, nearly invisible as he delivers this rare glimpse of greatness to the world that will never know him.

Matt Damsker is an author and critic, who has written about photography and the arts for the Los Angeles Times, Hartford Courant, Philadelphia Bulletin, Rolling Stone magazine and other publications. His book, "Rock Voices", was published in 1981 by St. Martin's Press. His essay in the book, "Marcus Doyle: Night Vision" was published in the fall of 2005. He currently reviews books for U.S.A. Today.

(Book publishers, authors and photography galleries/dealers may send review copies to us at: I Photo Central, 258 Inverness Circle, Chalfont, PA 18914. We do not guarantee that we will review all books or catalogues that we receive. Books must be aimed at photography collecting, not how-to books for photographers.)

Bassenge Holds Auction of Chinese Photos, 1890s-1950s, Plus Multi-Owner Sale in Berlin on June 4th

London Photograph Fair Changes Hands Again

Over 300 New Items Posted up for Sale on I Photo Central Web Site in Just the Last Three Months

Photo Book Reviews: America, London and Photographers in View

Share This